Jump to Recipe

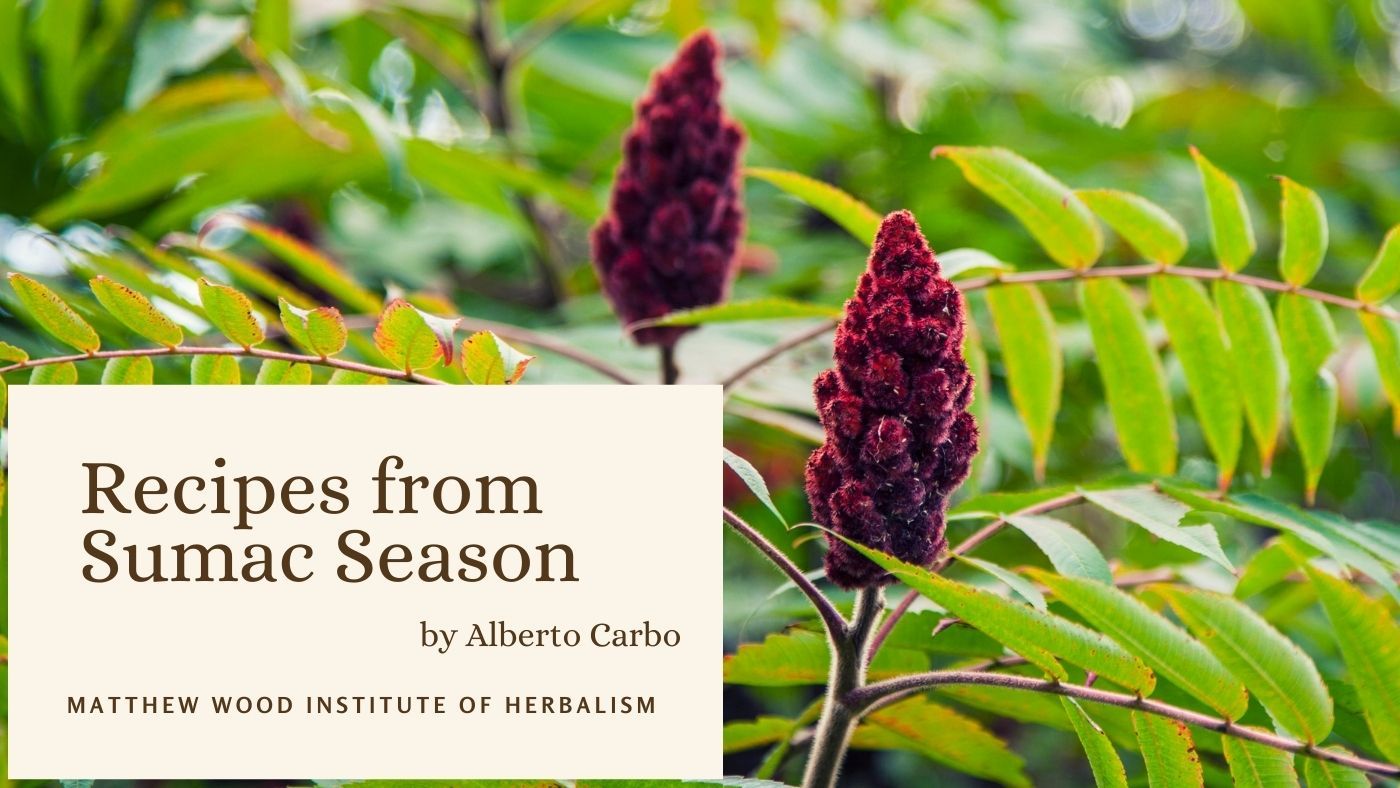

Staghorn sumac - Rhus typhina, is such a visually appealing plant to bump into! I remember when I first noticed its deep burgundy hues, thinking it looked soft and feeling so satisfied at verifying just how soft it was when I touched it, as well as finding the stem, also covered in soft faint hairs.

This was well before being interested in plants for medicinal purposes. I was not even aware of what this plant was called, nor did I know that it was the north American equivalent of the sumac spice from the middle east that I was familiar with.

When I found out its name, and that it was edible, I could hardly believe it. My first thoughts were ‘It’s everywhere!’. So, I set out to collect these beautiful specimens, excited to try making anything with them.

Luckily, thanks to a story about a mid-wedding-bouquet-disaster in late August (earwigs all over the head table, and in the food!), which my florist friend had enlightened me with, I learned that it is best to pick them in early August. Now that I have gathered them for several seasons, I can say that in my semi-northern (Ottawa, Canada) home, the perfect time is at the end of July and the beginning of August, although this is likely much sooner the further south you live.

These beautiful, velvety berries, start out green, and thanks to the heat of the summer, slowly turn deeper and deeper red, turning a dark shade of burgundy that just screams ‘flavonoids!’. Although it is important to gather staghorn sumac before too long to avoid them being infested with bugs, it is also important to wait long enough for the constituents to be sufficiently concentrated to make good medicine and/or a delicious treat. To check if they are ready, in late July or early August, I will lightly run my fingertip over a stag and then lick my finger. If the taste is sour like fresh lemon, it’s ready!

Years later, I learned that sumac is also used medicinally as a nourishing astringent for the urinary tract and for weak kidneys, when there is too much peeing during the day, nocturia, or nervous peeing. Staghorn sumac is beautifully sour and astringent. The sour taste is cooling to the system and is very welcome at this time of year as it cools you down while opening the pores, encouraging the body to release heat. Sumac has also been known to regulate blood sugars and is naturally high in vitamin C, vitamin A, flavonoids, and tannins.

Later on, I also learned from Matthew Wood and Chris McPadden in Herbs A-Z - Wolf and Deer Medicine, that sumac is deer medicine. They really do resemble velvety deer antlers! In that class, I also learned that sumac can be used as a remedy for poison ivy. I just love how you can continue to broaden your knowledge about every plant over the years. Learning from nature is never-ending!

Not only do the sumac berries resemble deer antlers, but deer also like to graze on these berries when they are ripe, and you can also catch them nibbling away in the frozen winter months when the sumac berries persist despite the barren branches all around.

Some differentiation:

Smooth Sumac – Rhus glabra, is interchangeable with staghorn sumac – Rhus typina, at least culinarily, in my experience. I have not used smooth sumac in a clinical setting. Smooth sumac looks very similar to staghorn sumac, but the berries are not as compactly clustered on the stems, and as its name suggests, the berries appear smoother, rather than the fuzzy appearance of the staghorn.

People can sometimes be weary of sumac because they have heard of poison sumac - Toxicodendron radicans (previously Rhus Toxicodendron), or poison ivy. While similar in name, these plants are quite easy to tell apart, especially when they have flowered.

Unlike the two species above, poison sumac has white berries (they will not turn red) that hang down, unlike the erect or upward pointing, crimson red berries of the smooth and staghorn sumac. Poison ivy (sumac), Toxicodendron radicans, also has small, white, four-point flowers. In addition, the leaves are quite different from each other – with poison sumac, you find three oval to diamond-shaped leaves, whereas with staghorn sumac you find anywhere between 9 and 31 lance-shaped leaves on a single stem.

An alcohol extraction yields a beautiful deep red and semi-viscous tincture, but its versatility in the kitchen is incredible. See some recipes further below that exemplify sumacs culinary versatility.

Check out the recipes below!

This was well before being interested in plants for medicinal purposes. I was not even aware of what this plant was called, nor did I know that it was the north American equivalent of the sumac spice from the middle east that I was familiar with.

When I found out its name, and that it was edible, I could hardly believe it. My first thoughts were ‘It’s everywhere!’. So, I set out to collect these beautiful specimens, excited to try making anything with them.

Luckily, thanks to a story about a mid-wedding-bouquet-disaster in late August (earwigs all over the head table, and in the food!), which my florist friend had enlightened me with, I learned that it is best to pick them in early August. Now that I have gathered them for several seasons, I can say that in my semi-northern (Ottawa, Canada) home, the perfect time is at the end of July and the beginning of August, although this is likely much sooner the further south you live.

These beautiful, velvety berries, start out green, and thanks to the heat of the summer, slowly turn deeper and deeper red, turning a dark shade of burgundy that just screams ‘flavonoids!’. Although it is important to gather staghorn sumac before too long to avoid them being infested with bugs, it is also important to wait long enough for the constituents to be sufficiently concentrated to make good medicine and/or a delicious treat. To check if they are ready, in late July or early August, I will lightly run my fingertip over a stag and then lick my finger. If the taste is sour like fresh lemon, it’s ready!

Years later, I learned that sumac is also used medicinally as a nourishing astringent for the urinary tract and for weak kidneys, when there is too much peeing during the day, nocturia, or nervous peeing. Staghorn sumac is beautifully sour and astringent. The sour taste is cooling to the system and is very welcome at this time of year as it cools you down while opening the pores, encouraging the body to release heat. Sumac has also been known to regulate blood sugars and is naturally high in vitamin C, vitamin A, flavonoids, and tannins.

Later on, I also learned from Matthew Wood and Chris McPadden in Herbs A-Z - Wolf and Deer Medicine, that sumac is deer medicine. They really do resemble velvety deer antlers! In that class, I also learned that sumac can be used as a remedy for poison ivy. I just love how you can continue to broaden your knowledge about every plant over the years. Learning from nature is never-ending!

Not only do the sumac berries resemble deer antlers, but deer also like to graze on these berries when they are ripe, and you can also catch them nibbling away in the frozen winter months when the sumac berries persist despite the barren branches all around.

Some differentiation:

Smooth Sumac – Rhus glabra, is interchangeable with staghorn sumac – Rhus typina, at least culinarily, in my experience. I have not used smooth sumac in a clinical setting. Smooth sumac looks very similar to staghorn sumac, but the berries are not as compactly clustered on the stems, and as its name suggests, the berries appear smoother, rather than the fuzzy appearance of the staghorn.

People can sometimes be weary of sumac because they have heard of poison sumac - Toxicodendron radicans (previously Rhus Toxicodendron), or poison ivy. While similar in name, these plants are quite easy to tell apart, especially when they have flowered.

Unlike the two species above, poison sumac has white berries (they will not turn red) that hang down, unlike the erect or upward pointing, crimson red berries of the smooth and staghorn sumac. Poison ivy (sumac), Toxicodendron radicans, also has small, white, four-point flowers. In addition, the leaves are quite different from each other – with poison sumac, you find three oval to diamond-shaped leaves, whereas with staghorn sumac you find anywhere between 9 and 31 lance-shaped leaves on a single stem.

An alcohol extraction yields a beautiful deep red and semi-viscous tincture, but its versatility in the kitchen is incredible. See some recipes further below that exemplify sumacs culinary versatility.

Check out the recipes below!

Sumac Recipes

As always make sure to forage for plants away from roads and pollution as much as possible. Never overharvest any plant, as they are of course not only here for our enjoyment, but also here for the insects, bees, and birds. Have fun out there!

**Disclaimer**

The information provided in this digital content is not medical advice, nor should it be taken or applied as a replacement for medical advice. Matthew Wood, the Matthew Wood Institute of Herbalism, ETS Productions, and their employees, guests, and affiliates assume no liability for the application of the information discussed.

The information provided in this digital content is not medical advice, nor should it be taken or applied as a replacement for medical advice. Matthew Wood, the Matthew Wood Institute of Herbalism, ETS Productions, and their employees, guests, and affiliates assume no liability for the application of the information discussed.