For those that live in temperate, snowy climates, you may be lucky enough to see a plant-based wonder. Who am I kidding - all plants have wonders. However, I find this one to be especially unique because this species can grow up through the snow. The plant is Skunk Cabbage, or Symplocarpus foetidus.

The question on most folks’ minds is: how does Skunk Cabbage grow in the snow?

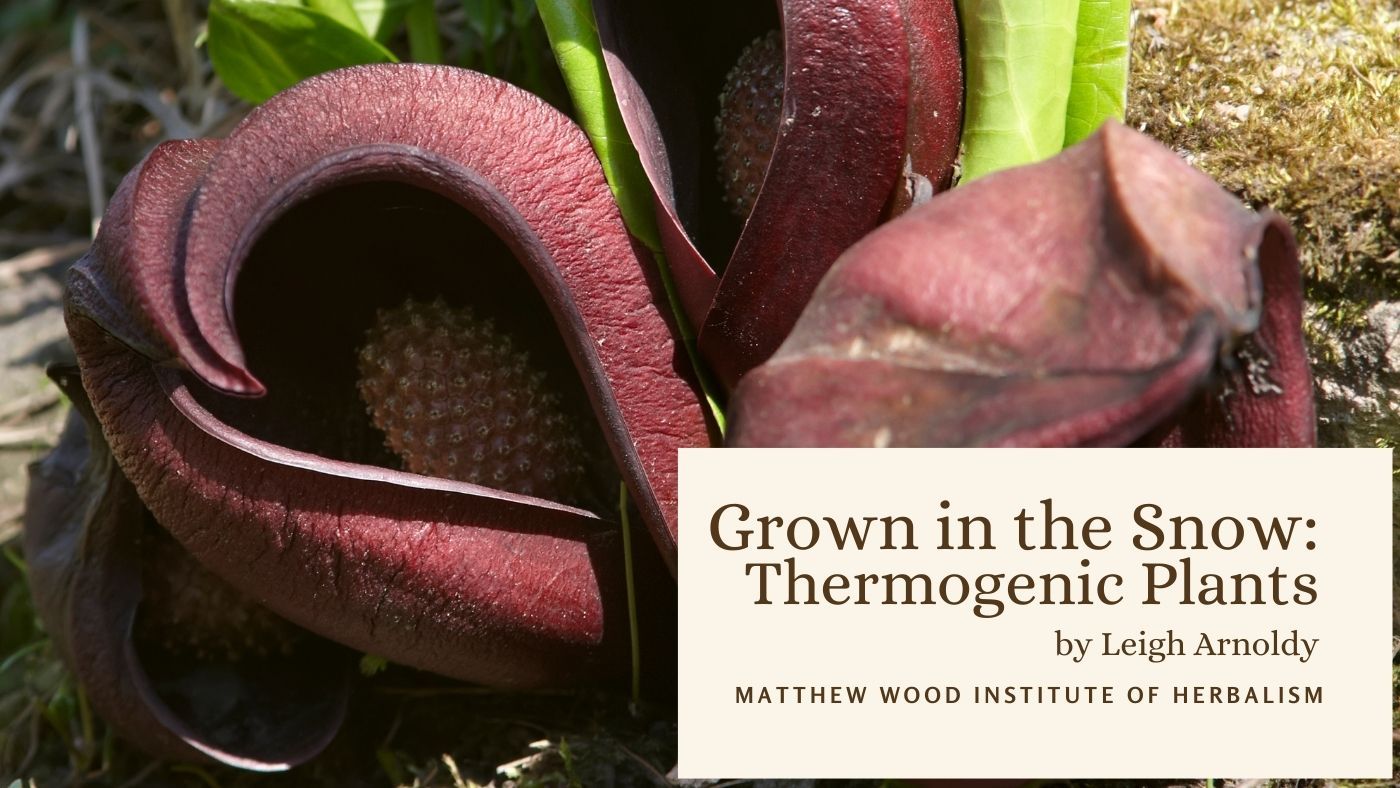

Skunk Cabbage is classified as a thermogenic - or heat-producing plant. One way Skunk Cabbage can create heat is by manipulating the normal process of carbohydrate oxidation. It can regulate its own temperature through its spadix, the spiky “head” that is surrounded by a cloak-like spathe.

But why is the temperate Skunk Cabbage thermogenic?

Skunk Cabbage is in the Arum Family (Araceae), which has its roots in more tropical climates (pun completely intended). This family includes the modern-day plant wonder called the Corpse Flower, Amorphophallus titanum. Both plants are even saddled with particularly odiferous names. And that might be the key to understanding the “why” of their thermogenics.

With a few fascinating exceptions, most plants need pollinators; the Arums are no different in this respect. What is unique is that the particular scent that they broadcast (skunk, corpse, etc.) is made much more volatile by the heating process, bringing in fly pollinators. This makes complete sense in the tropical region, where flies are abundant year-round.

The process of thermogenesis takes huge amounts of energy resources from the plant. Is it worth it for the flies that aren’t present in a Minnesota February? In a study of a Skunk Cabbage’s cousin, the Eastern Asian Skunk Cabbage (Symplocarpus renifolius), there is a suggestion that heat correlates with abundant mitochondria (and we all know that the mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell). Abundant mitochondria make genetic expression and cellular respiration flourish, which all happens in the female stage of the plant’s inflorescence development; it is proposed that this is the process that helps the plant transition to its next stage of development. In the case of the Corpse Flower, it is proposed that the pollinators get a side benefit - the night-time pollinators may be benefited from the warmth of the plant. Right now, it’s not certain exactly why Skunk Cabbage and other Arums do what they do, but the ideas are promising.

How could this heating trait define Skunk Cabbage as an herb?

I’m a huge fan of the Doctrine of Signatures, a theory that plant behavior, visual presentation, environment, and other attributes give you a clue as to how those properties can be utilized as plant medicine. Since Skunk Cabbage is able to generate its own heat, it naturally has the intelligence to navigate this issue and can help our bodies with heat regulation or bring heat to needed areas. This may be helpful in utilizing heat to help unstick old phlegm.

The environment of Skunk Cabbage is the swampy, damp backwater areas. What parts of our body might be swampy or damp? These two signatures combined give us an herb that has its intelligence in dealing with heat in our body’s swamps: that could be the lungs, kidneys, spleen, or lymphatics.

Bears are reported to eat the young leaves before the calcium oxalates get too much to digest. This may distinguish it as a Bear Medicine but in a way I’ve never thought about before. Most Bear Medicines are brown, furry, oily roots that can help with adrenal function, and are generally warming in nature. Other Bear Medicines include cooling fruits that bears enjoy, like blueberries; these are used to help cool off during hot summer days.

Skunk Cabbage doesn’t seem to fit either of these categories. However, it would make sense as a lymphatic stimulant after a winter’s torpor, the true "hibernation" state of bears that involves waking in case of danger or the need to forage. The word "torpor" itself is also a damp tissue state which Herbalist Matthew Wood calls "stagnation." This situation is also reminiscent of the spectrum of energy conservation that both plant and animal experience; the bear conserves it and the Skunk Cabbage expends it.

Herbalist Seán O’Donoghue illustrates that Skunk Cabbage and Bears use the same biochemistry to "wake up." He then speculates that there may be a connection to awakening from the hypothyroid state. Matthew Wood points out that, indeed, the thyroid is what generates heat in our bodies. Many people with hypothyroid tendencies will often experience sluggishness and sleepiness, as well as weight gain and cooler body temperatures. Check out the clip on thermogenetic plants.

Many Arums like Skunk Cabbage are associated with the Throat: Homeopath William Boericke used Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arum Triphyllum) for hoarseness, and "the Clergyman’s sore throat," which would be due to spending a lot of time pontificating. In both, the spathe looks like a mouth and the spadix looks like the pendulum-like uvula.

The spadix looks like a spiky little ball, not unlike the shape of a virus. As I’ve heard Matthew Wood say many times, "nature doesn’t waste a shape;" this plant understands the geometry of a virus. This could potentially help with viruses that tend to hang out in those same, swampy areas, causing heat or low-grade fevers.

More connections

The shape of the spathe is reminiscent of the almond-like vesica piscis, or "bladder of the fish." Not only do we have a wet, cold fish, but we have a representation of the bladder. This shape definitely has connections to the element of water. The shape itself is formed at the union of two overlapping circles. The mathematical implications of this shape lie in its ability to construct a triangle with its width being the square root of 3 - the number of creation.

The vesica piscis is also present in the 11th and 12th century Sheela na gig, the carvings of the woman with the vulva. This is also the general shape of the pineal. The pineal is associated with the third eye or an "otherly" type of knowing. The pituitary also has a connection to the night, being in charge of melatonin production, sleep, and other body cycles, which recalls the state of sleep and torpor of Bear Medicine from earlier. The pineal is physically hidden, buried in the deep recesses of our brain, protected by the sheath-like corpus callosum. The corpus callosum unites both hemispheres of the brain, recalling the image of two circles overlapping to create the vesica piscis. Overall, we have a shape that is connected to women, water, and wisdom, as well as the part of the creative process that is hidden, just before it enters into existence.

How do women, water, and wisdom connect to the plant properties of Skunk Cabbage?

The Skunk Cabbage is hooded, like its Arum cousins. It’s hiding this mysterious process of thermogenesis, a caricature of the alchemist, bent over her work, creating something behind the scenes. Just what exactly that is, I can’t say. Scientists are still baffled at how the Arums guard their cellular secrets. Even the Corpse Flower releases its pollen during the sanctuary of the night.

We can’t forget one of the ultimate processes of hidden creation: life. The image of the spathe enclosing the spadix is very akin to the womb and fetus. Combined with the symbolism of the vulva, the timing and cycles of the pituitary, the number of creation, and the suggestion of genetic activity, this could be utilized for an energetically cold womb.

The Skunk Cabbage could be linked to genetic information that has, up to now, been a mystery. Maybe that means we need to spend time journeying with this plant. After all, the plant has journeyed a long way from its own equatorial home to be with us.

The question on most folks’ minds is: how does Skunk Cabbage grow in the snow?

Skunk Cabbage is classified as a thermogenic - or heat-producing plant. One way Skunk Cabbage can create heat is by manipulating the normal process of carbohydrate oxidation. It can regulate its own temperature through its spadix, the spiky “head” that is surrounded by a cloak-like spathe.

But why is the temperate Skunk Cabbage thermogenic?

Skunk Cabbage is in the Arum Family (Araceae), which has its roots in more tropical climates (pun completely intended). This family includes the modern-day plant wonder called the Corpse Flower, Amorphophallus titanum. Both plants are even saddled with particularly odiferous names. And that might be the key to understanding the “why” of their thermogenics.

With a few fascinating exceptions, most plants need pollinators; the Arums are no different in this respect. What is unique is that the particular scent that they broadcast (skunk, corpse, etc.) is made much more volatile by the heating process, bringing in fly pollinators. This makes complete sense in the tropical region, where flies are abundant year-round.

The process of thermogenesis takes huge amounts of energy resources from the plant. Is it worth it for the flies that aren’t present in a Minnesota February? In a study of a Skunk Cabbage’s cousin, the Eastern Asian Skunk Cabbage (Symplocarpus renifolius), there is a suggestion that heat correlates with abundant mitochondria (and we all know that the mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell). Abundant mitochondria make genetic expression and cellular respiration flourish, which all happens in the female stage of the plant’s inflorescence development; it is proposed that this is the process that helps the plant transition to its next stage of development. In the case of the Corpse Flower, it is proposed that the pollinators get a side benefit - the night-time pollinators may be benefited from the warmth of the plant. Right now, it’s not certain exactly why Skunk Cabbage and other Arums do what they do, but the ideas are promising.

How could this heating trait define Skunk Cabbage as an herb?

I’m a huge fan of the Doctrine of Signatures, a theory that plant behavior, visual presentation, environment, and other attributes give you a clue as to how those properties can be utilized as plant medicine. Since Skunk Cabbage is able to generate its own heat, it naturally has the intelligence to navigate this issue and can help our bodies with heat regulation or bring heat to needed areas. This may be helpful in utilizing heat to help unstick old phlegm.

The environment of Skunk Cabbage is the swampy, damp backwater areas. What parts of our body might be swampy or damp? These two signatures combined give us an herb that has its intelligence in dealing with heat in our body’s swamps: that could be the lungs, kidneys, spleen, or lymphatics.

Bears are reported to eat the young leaves before the calcium oxalates get too much to digest. This may distinguish it as a Bear Medicine but in a way I’ve never thought about before. Most Bear Medicines are brown, furry, oily roots that can help with adrenal function, and are generally warming in nature. Other Bear Medicines include cooling fruits that bears enjoy, like blueberries; these are used to help cool off during hot summer days.

Skunk Cabbage doesn’t seem to fit either of these categories. However, it would make sense as a lymphatic stimulant after a winter’s torpor, the true "hibernation" state of bears that involves waking in case of danger or the need to forage. The word "torpor" itself is also a damp tissue state which Herbalist Matthew Wood calls "stagnation." This situation is also reminiscent of the spectrum of energy conservation that both plant and animal experience; the bear conserves it and the Skunk Cabbage expends it.

Herbalist Seán O’Donoghue illustrates that Skunk Cabbage and Bears use the same biochemistry to "wake up." He then speculates that there may be a connection to awakening from the hypothyroid state. Matthew Wood points out that, indeed, the thyroid is what generates heat in our bodies. Many people with hypothyroid tendencies will often experience sluggishness and sleepiness, as well as weight gain and cooler body temperatures. Check out the clip on thermogenetic plants.

Many Arums like Skunk Cabbage are associated with the Throat: Homeopath William Boericke used Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arum Triphyllum) for hoarseness, and "the Clergyman’s sore throat," which would be due to spending a lot of time pontificating. In both, the spathe looks like a mouth and the spadix looks like the pendulum-like uvula.

The spadix looks like a spiky little ball, not unlike the shape of a virus. As I’ve heard Matthew Wood say many times, "nature doesn’t waste a shape;" this plant understands the geometry of a virus. This could potentially help with viruses that tend to hang out in those same, swampy areas, causing heat or low-grade fevers.

More connections

The shape of the spathe is reminiscent of the almond-like vesica piscis, or "bladder of the fish." Not only do we have a wet, cold fish, but we have a representation of the bladder. This shape definitely has connections to the element of water. The shape itself is formed at the union of two overlapping circles. The mathematical implications of this shape lie in its ability to construct a triangle with its width being the square root of 3 - the number of creation.

The vesica piscis is also present in the 11th and 12th century Sheela na gig, the carvings of the woman with the vulva. This is also the general shape of the pineal. The pineal is associated with the third eye or an "otherly" type of knowing. The pituitary also has a connection to the night, being in charge of melatonin production, sleep, and other body cycles, which recalls the state of sleep and torpor of Bear Medicine from earlier. The pineal is physically hidden, buried in the deep recesses of our brain, protected by the sheath-like corpus callosum. The corpus callosum unites both hemispheres of the brain, recalling the image of two circles overlapping to create the vesica piscis. Overall, we have a shape that is connected to women, water, and wisdom, as well as the part of the creative process that is hidden, just before it enters into existence.

How do women, water, and wisdom connect to the plant properties of Skunk Cabbage?

The Skunk Cabbage is hooded, like its Arum cousins. It’s hiding this mysterious process of thermogenesis, a caricature of the alchemist, bent over her work, creating something behind the scenes. Just what exactly that is, I can’t say. Scientists are still baffled at how the Arums guard their cellular secrets. Even the Corpse Flower releases its pollen during the sanctuary of the night.

We can’t forget one of the ultimate processes of hidden creation: life. The image of the spathe enclosing the spadix is very akin to the womb and fetus. Combined with the symbolism of the vulva, the timing and cycles of the pituitary, the number of creation, and the suggestion of genetic activity, this could be utilized for an energetically cold womb.

The Skunk Cabbage could be linked to genetic information that has, up to now, been a mystery. Maybe that means we need to spend time journeying with this plant. After all, the plant has journeyed a long way from its own equatorial home to be with us.

References

- Boericke M.D., W. (1927). Materia Medica with Repertory (Ninth Edition). Boericke & Tafel, Inc.

- Corpse Flowers. (n.d.). United States Botanic Garden. Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://www.usbg.gov/gardens-plants/corpse-flowers

- Corpus Callosum—An overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/corpus-callosum

- couchiching. (2015, April 13). Skunk cabbage; a warm-blooded plant? Couchiching Conservancy. https://couchichingconserv.ca/2015/04/13/skunk-cabbage-a-warm-blooded-plant/

- Do Bears Really Hibernate? (n.d.). Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://www.nationalforests.org/blog/do-bears-really-hibernate

- Ito-Inaba, Y. (2014). Thermogenesis in skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus renifolius): New insights from the ultrastructure and gene expression profiles. Advances in Horticultural Science, 28, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.13128/ahs-22797

- Johnson, K. (2019, August 27). Turning up the heat: The alternative oxidase pathway drives thermogenesis in cycad cones. Plantae. https://plantae.org/turning-up-the-heat-the-alternative-oxidase-pathway-drives-thermogenesis-in-cycad-cones/

- Korotkova, N., & Barthlott, W. (2009). On the thermogenesis of the Titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum). Plant Signaling & Behavior, 4(11), 1096–1098.

- Minorsky, P. V. (2003). The Hot and the Classic. Plant Physiology, 132(1), 25–26. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.900071

- Pineal Gland: What It Is, Function & Disorders. (n.d.). Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23334-pineal-gland

- Sheela na gig. (2022). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sheela_na_gig&oldid=1126109431

- Skunk cabbage, Symplocarpus foetidus. (n.d.). Wisconsin Horticulture. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/skunk-cabbage-symplocarpus-foetidus/

- Symplocarpus foetidus (Skunk Cabbage): Minnesota Wildflowers. (n.d.). Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://www.minnesotawildflowers.info/flower/skunk-cabbage

- The Pineal Gland and Melatonin. (n.d.). Retrieved February 20, 2023, from http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/endocrine/otherendo/pineal.html

- Vesica piscis. (2023). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Vesica_piscis&oldid=1132827567

- Warm-Blooded Plants. (n.d.). Damn Interesting. Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://www.damninteresting.com/warm-blooded-plants/

- Wood, M. (2008). The Earthwise Herbal: A Complete Guide to Old World Medicinal Plants. North Atlantic Books.

**Disclaimer**

The information provided in this digital content is not medical advice, nor should it be taken or applied as a replacement for medical advice. Matthew Wood, the Matthew Wood Institute of Herbalism, ETS Productions, and their employees, guests, and affiliates assume no liability for the application of the information discussed.

The information provided in this digital content is not medical advice, nor should it be taken or applied as a replacement for medical advice. Matthew Wood, the Matthew Wood Institute of Herbalism, ETS Productions, and their employees, guests, and affiliates assume no liability for the application of the information discussed.